Glioblastoma: a new study sheds light on the mechanism by which this tumour invades tissues

The study, published in Neuro Oncology, discovered a mechanism that enhances glioblastoma’s ability to migrate and infiltrate tissues, paving the way for future therapies.

Glioblastoma is a very aggressive form of brain tumor: even today, people diagnosed with it have an average survival of between 10 and 13 months due to current treatments. Less than 10% of patients survive five years after diagnosis. One of the challenges that makes this condition particularly difficult to treat is the high incidence of recurrences. Glioblastoma cells tend to infiltrate surrounding tissue, and despite surgical removal and treatment with chemotherapy and radiation, they can trigger tumor regrowth.

A new study published in Neuro Oncology, led by Matteo Tamborini, Valentino Ribecco, and Elisabetta Stanzani, investigated the mechanisms that regulate glioblastoma cell infiltration into surrounding tissue, successfully demonstrating its function in various contexts: in vitro, in vivo, and on organoids that three-dimensionally replicate human nervous tissue. Humanitas’ research in the neuro-oncology field is also possible thanks to the support of the Humanitas Foundation for Research and collaboration with clinical groups led by Federico Pessina and Marco Riva (Neurosurgery) and Letterio Salvatore Politi (Radiodiagnostics).

“These results are important because they identify some cellular mechanisms that seem to underlie the invasiveness of one of the most aggressive tumors,” explains Michela Matteoli – Director of the Neuroscience Program at the IRCCS Istituto Clinico Humanitas.

How glioblastoma spreads

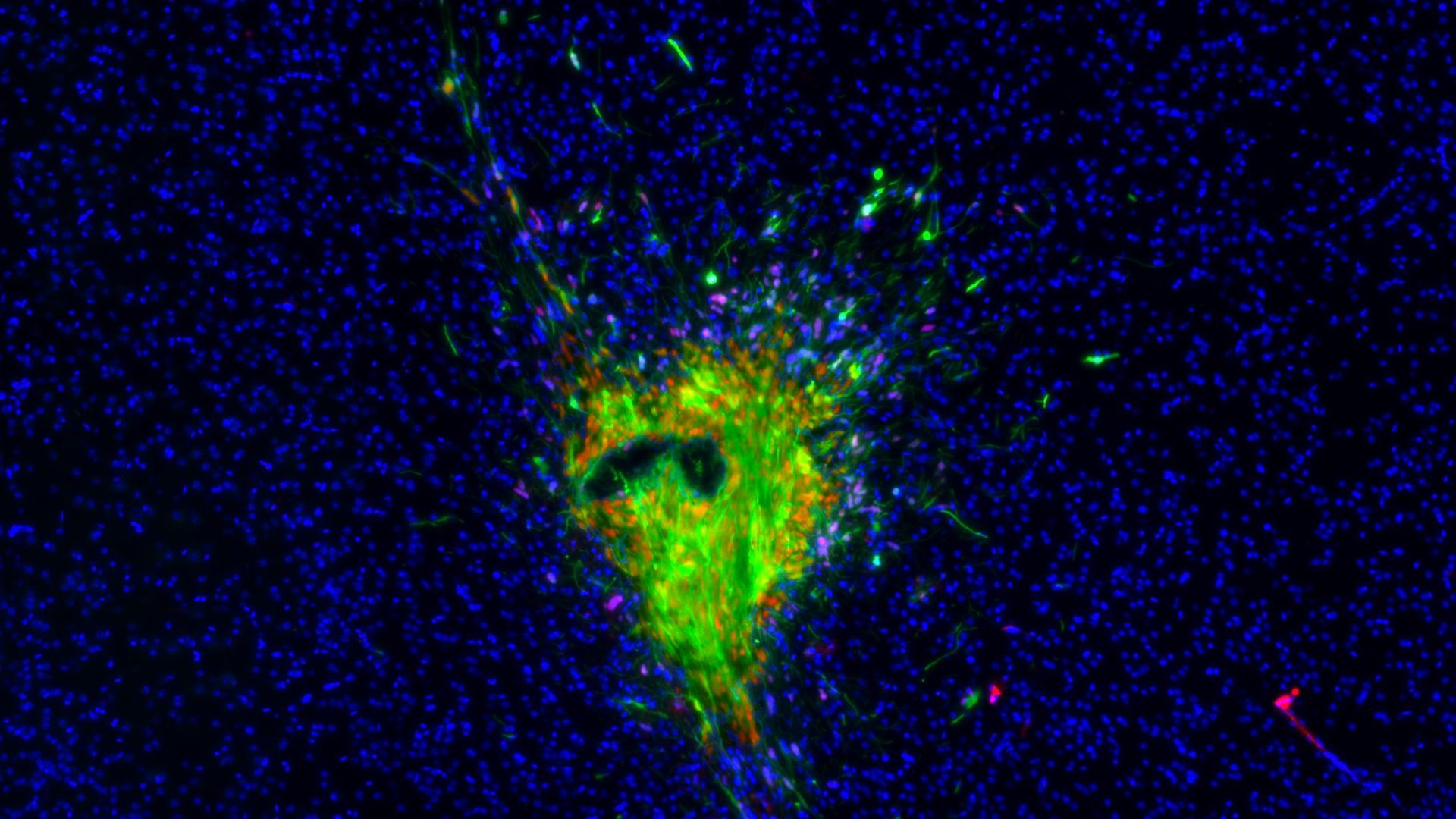

The Humanitas research team focused on one of the strategies used by glioblastoma tumor cells to communicate with each other and their surrounding environment: the production of extracellular vesicles. These extracellular vesicles form by budding from the tumor cell membrane and contain information derived from the cell itself. Once formed, the vesicles can fuse with other cells in the surrounding tissue, transmitting signals that can alter their functions. Specifically, Tamborini, Ribecco, Stanzani, and their colleagues, including Lorena Passoni and Giuseppe Martano from Humanitas, focused on the effect of these vesicles on the tumor cells themselves, discovering that the vesicles significantly increase their ability to migrate. The vesicles produced by the tumor thus facilitate and enhance its infiltration into surrounding tissue.

“One of the questions we asked ourselves is how the vesicle imparts this ability to the receiving cell,” explains Matteo Tamborini. By analyzing the cells after the vesicles were administered, the researchers identified a key protein involved in the process, Connexin 43. “It is through this protein that the microvesicles activate the cell motility signal in the tumor: a potential therapeutic target to slow down its migration.”

A collaborative effort

The Neuroscience Program, led by Michela Matteoli, has been working for years in collaboration with the neuro-surgeons of Humanitas to collect tumor tissues from patients with glioblastoma: a collaboration that has allowed the development of cell lines derived from patients. “These are tumor stem cells,” explains Michela Matteoli. “Today, thanks to this collaboration, we have a bank with more than 60 human cell lines derived from patients.” This cell line bank has been crucial for the researchers involved in the study published in Neuro Oncology.

“The collaboration with Humanitas’ neurosurgeons has been invaluable,” explains Elisabetta Stanzani, “because it provided us not only with tumor tissue from the patient but also the so-called surgical aspirate, a crucial resource for us as it contains the microvesicles produced by the tumor, released into the tissue in a clinically relevant context.” Using tumor stem cells collected from the patient, the researchers generated the cell lines studied in culture. They then used the vesicles isolated from the surgical aspirate to activate the tumor cell lines, demonstrating how these vesicles can influence the progression of the disease.

An important part of the research was conducted in collaboration with Simona Lodato, who leads the Neurodevelopmental Biology Lab at the IRCCS Istituto Clinico Humanitas. Lodato’s lab produced brain organoids formed from three-dimensional cultures of human cells, into which the tumor itself was integrated: this allowed the researchers to analyze the mechanism behind glioblastoma spread not only in vitro and in experimental models but also in a 3D architecture composed of human neuronal cells.

“The vesicles play a strong role in inducing glioblastoma migration,” comments Michela Matteoli. “This means that some of the molecular mechanisms we have identified through this collaborative study – from the release of the vesicles to the interaction with the tumor via connexin – could be used as pharmacological targets in future therapies.”